~~~it’s a pandemic~~~

Stigma as a pre-existing condition

Dear friends,

Oops. What happened to April? (Or, erm, May?)

As Mexico City gets ready to ‘open up’ again, I think about the disaster I was nervously anticipating in March.

Back then, the international news was leaking bodies from a tear that tracked from Wuhan to Milan to New York, coming seemingly ever-closer to home.

How could we expect it to be anything but ‘even worse’ in Mexico?

Mexico, where hunger, poverty and violence is widespread and public institutions are weak, where surely the resources available to society to plan for economic management, to demand people take the right measures to slow the spread, to prevent mass death from an ~~~actual pandemic~~~, would be too scarce to hold off total collapse? It did not help that President AMLO sounded so disconnected, touring Acapulco beach and saying we should still greet each other with hugs and kisses. Did anyone have a handle on what was coming?!

All the sad and worried emojis have not stopped being a daily feature of my text messages, let me tell you. But now, some two months and two self-administered haircuts later, I also wonder if some of concern might be attributed to a kind of generalised geopolitical anxiety, related to how Mexico often appears in the international game of tropes: a ‘developing’ or ‘third world’ country; eternally ungovernable, a non-specifically endemic mess.

If such a bias was in your air already, it may have found some confirmation to bind to in accounts of Mexico’s handling of the pandemic published between May 8-13 in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, El País, Sky, and Vox.

Sky’s piece was arguably the blurst. In the building I live in we actually wondered if it was their journalists we’d seen outside in the street the day before the story came out. There’d been a camera crew on the corner that morning, lenses trained on the government-run funeral parlour across the road. Whoever they were, they wouldn’t have captured much action: to prevent contagion, bodies of course are being delivered around the back and taken off for incineration and internment, with few witnesses. At any rate, while Sky managed to scoop that Mexico is a majority-poor country facing a global pandemic, the multimedia reporting does not explain the story much further save to hone in on the horror. Stuart Ramsay, Sky’s UK-based correspondent bawls out “a city in denial” where “people live cheek by jowl in vast slums with no running water, families are extended and close, and there is scant regard for social distancing”.

“Just from witnessing the shocking numbers of hearses waiting to take the latest victims of the virus to be cremated”, writes Ramsay, “it was clear that officialdom would fail to provide us with the real details of what is going on here”. Visuals of stacked coffins, crowded streets, and overactive incinerators further illustrate a tale of terminal neglect.

In all the articles mentioned above, the number of people in Mexico who are dying from covid19, alongside an alleged cover-up of real numbers of cases and deaths by authorities, appears as the cover-all metric for understanding how the pandemic is going down in this country, brought to you by the fearlessness of the international press. The virus is bad in Mexico, because Mexico is bad: allow us to show you, because they won’t.

Is it bad tho

The truth is absolutely that thousands in Mexico are contracting covid19 and thousands are dying from it. The official number of dead reached 9,930 people today, with 90,664 registered cases. Low rates of testing, high rates of poverty, low access to quality education and income protection, an under-resourced public health system, and mendacious shenanigans by media and political leaders probably haven’t helped these numbers. Indeed, these issues are being repeatedly pointed out by independent media outlets within Mexico who are doing their own investigations into the true cost of the pandemic to Mexico and the underlying conditions thereof. In one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist, networks like Pie de Página and Animal Político are holding authorities to account and talking to hospital workers and funeral directors.

Hundreds of the dying are health workers in the public system, doing their best where sometimes access to masks and hand sanitizer were long gone before the advent of covid19. Others are workers on Mexico’s border with the US, where factories have been producing ventilators bound for hospitals in North America and Europe. Many, doubtless more than we will ever know, are dying due to a co-morbidity like diabetes or respiratory disease or hypertension. Many of these, and many more again, are dying as patients of the public health system–through which all Mexican citizens are guaranteed medical care at no cost, and that is run down to the point where hospital workers, at likely personal cost, are telling legacy US media about things like patients dying in their beds from their breathing tubes being clogged because there was no staff to attend them. Many of the dead are, or will be, workers in the country’s majority informal economy who cannot not go out to earn enough money to live (nb. unlike many other countries in Central and South America, the Mexican government has not actively enforced restrictions on movement).

Which is not to mention the Mexicans dying from covid19 in the US, returning to their villages as ash. Or the families on repeat visits to the cemetery, to bury one more who has died. Or, or, or.

And, yes: Mexico already has shocking rates of homicide (linked to the activities powerful organised crime syndicates), deadly violence against women, and impunity. At least 61,000 people have disappeared since 2006, and nearly every month brings news of another clandestine gravesite discovery. One in every 10 Mexicans lives in extreme poverty, and high rates of diabetes, hypertension and obesity are also linked to early deaths. Structural adjustment obligations, free trade agreements, and the war on drugs have all powerfully altered the everyday lives of ordinary people in Mexico in the past four decades; experienced by many as external forces over which they have minimal control.

Against these pre-existing, transnationally-networked conditions, about which little has been done, what does it mean to count deaths from a global pandemic in Mexico?

Epidemio-logic?

You wouldn’t read about it, but Mexico has legit chops in pandemic response. The Mexican federal government approach to covid19 has been led by sub-secretary of health Dr Hugo López-Gatell, a Johns Hopkins-trained epidemiologist, who has been leading popular nightly press briefings that are televised and streamed to the public. Gatell has recently joined the World Health Organization’s expert team on international health regulations, where he will contribute advice on population health management.

Mexico has been here before. It is far from the first time the country’s political leaders have been confronted with the challenge of staving off public health disaster within a massive population and a huge economy; such as in the 1985 and 2017 earthquakes and the H1N1 (‘swine flu’) pandemic in 2009. The ‘sentinel system’ of disease surveillance that was used then identified the first cases of covid19 in the country in February. Going further back, Mexico led the world in the mid-1980s responding to the HIV/AIDS epidemic–while, it might be noted, US President Ronald Reagan was calling the disease “the gay plague” and refusing to address it.

All the above background should give cause for us international reporters to assume there is a historicised logic to how Mexican society is responding to the pandemic, in which the number of deaths from this new virus is a critically important metric and also might not be the only one. To be sure, with their thirst to master the death/case rate and call out the authorities, the international media reports of mid-May had nothing to say, for example, about hospital capacity–a pandemic management measure on which, as Lucina Melesio reported in The Washington Post last week, Mexico City (where the majority of infections are occurring) at least has succeeded, up until now. Within a period where high levels of infections were anticipated (the week of May 15), Melesio found that the city’s general public hospital beds had close to 80% occupancy, with almost 70% of intensive care beds with ventilators for covid19 patients occupied, and hospitals were still admitting patients.

Isn’t this why, all around the world, nations have been working hard to ‘flatten the curve’ – so that our societies and systems do not, at least on optics, run out of resources to treat the sick and bury the dead? As an indicator of Mexico’s handling of the pandemic, hospital preparedness adds explanatory power to the body count–marking Mexico’s constitutional right to no-cost health care, allowing for interrogation (as Melesio does, and that the New York Times has now done too) of the quality of and access to that care, and perhaps revealing a little more about the political wagers being made by those in charge of the response.

Without nuance, without care for context, international reporting can so easily simply repeat the construction of Mexico, or anywhere subject to geopolitical stigma, in the global imagination as a place marked by little more than ahistorical scarcity and ghoulish loss of life – a place that, moreover, can only be comprehended through the superior oculus of the ‘developed’ world. Given that said world is still where much of the world proper’s wealth is stashed, we might also remain vigilant on whose interests are served by certain versions of the Mexico-as-natural-disasterscape story.

Further reading:

- Africa is not waiting to be saved from the coronavirus, Nanjala Nyabola, The Nation ; Why are Africa's coronavirus successes being overlooked?, Afua Hirsch, The Guardian

- Who Will be Held Responsible for The Loss of Life? The Virus?, Paulo Jorge Gomes Pereira, RioOnWatch

- We feed you: migrant farm workers in Australia, The Saturday Paper

- ‘In each other’s shadows’: Behind Irish outpouring of relief for Navajo, Christian Science Monitor

While you weren’t looking, with Amy McKinnon - the news we’re missing in the time of covid19, Foreign Policy

And:

- How Western media would cover Minneapolis if it happened in another country ; Aboriginal activists in Australia are sending messages of support to George Floyd protesters

Till next time.

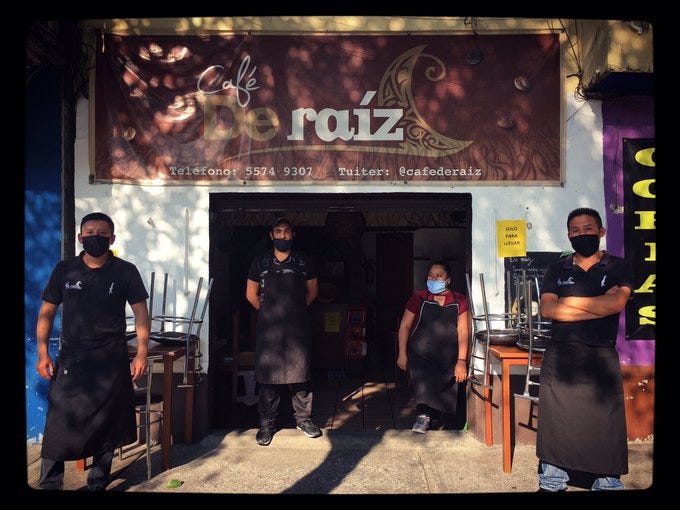

I'm signing off with a picture of Poncho, Nico, Pola and Cheto, the team behind Café de Raíz (Roots Café) located in Roma Norte, a central neighbourhood of Mexico City where covid19 measures have left many local businesses and mobile street vendors with seriously reduced income. Café de Raíz is running a daily ‘Menu Solidario’ (Solidarity Menu), where, for 50 pesos (about 2.50USD) you can buy a three-course lunch and the café will also give the same meal to someone who needs it. “Donde come uno, comen todos” - “Where one eats we all eat”, says Pola, who has also been co-ordinating a pool of people to help elderly neighbours needing help with shopping and other such tasks in this time. “This is a community-based effort to resist the pandemic”.

Very best to you all,

Ann.